SHI 10.8.25 – Zero-Sum Game?

SHI 10.2.25 – $2 Trillion

October 2, 2025

SHI 10/15/25: Bubble? Transformative? Existential?

October 15, 2025“Is this a bubble?”

This blog is the second of a multi-blog series on artificial intelligence.

More specifically, this series will center on the question of if a bubble

has – or is – forming within the financial markets.

My first blog framed the discussion. Today, we will debate divergent facts and ideas.

“

Bubble talk.”

“

Bubble talk.”

If you missed my first blog, here’s a link (right click, open in a new tab):

https://steakhouseindex.com/shi-10-2-25-2-trillion/

And in a third, and final blog on this topic, I will share and support my answer to the question – Is this “AI thing” a bubble?

Welcome to this week’s Steak House Index update.

If you are new to my blog, or you need a refresher on the SHI10, or its objective and methodology, I suggest you open and read the original BLOG: https://www.steakhouseindex.com/move-over-big-mac-index-here-comes-the-steak-house-index/

Why You Should Care: The US economy and US dollar are the bedrock of the world’s economy. But is the US economy expanding or contracting?

Expanding.

The ‘real’ growth rate — the number most often touted in the mainstream media — was 3% in the last quarter. In “current dollar” terms, US annual economic output rose to $30.331 trillion.

According to the World Bank, the world’s annual GDP expanded to over $111 trillion in 2024. Further, IMF expects global GDP to reach almost $132 trillion by 2030. The US? Various forecasts project about $37 trillion for American GDP in 2030 — I believe it could be even higher.

America’s GDP remains around 28% of all global GDP. Collectively, the US, the European Common Market, and China generate about 70% of the global economic output. These are the 3 big, global players. They bear close scrutiny.

The objective of this blog is singular.

It attempts to predict the direction of our GDP ahead of official economic releases. Historically, ‘personal consumption expenditures,’ or PCE, has been the largest component of US GDP growth — typically about 2/3 of all GDP growth. In fact, the majority of all GDP increases (or declines) usually results from (increases or decreases in) consumer spending. Consumer spending is clearly a critical financial metric. In all likelihood, the most important financial metric. The Steak House Index focuses right here … on the “consumer spending” metric. I intend the SHI10 is to be predictive, anticipating where the economy is going – not where it’s been.

Taking action: Keep up with this weekly BLOG update. Not only will we cover the SHI and SHI10, but we’ll explore “fun” items of economic importance. Hopefully you find the discussion fun, too.

If the SHI10 index moves appreciably -– either showing massive improvement or significant declines –- indicating growing economic strength or a potential recession, we’ll discuss possible actions at that time.

The Blog:

King Henry the 8th is famous for a number of reasons.

But you’re probably unfamiliar with this one: He’s the undisputed father of “inflation” resulting from a currency debasement.

That’s right. He invented it. According to a Gregory Clark, a historian at the Bank of England, back in the 1500s, a “standard basket of goods” in England essentially cost the same as it did 300 years prior. And 200 years. And a hundred. But then something changed.

Price inflation, something never before experienced, became unstoppable. In 50 years, prices doubled across England. About the same time, prices in France, Holland, Italy and Russia began to increase between 3-5% each year.

By 1590, prices all across Europe were increasing by at least 3% per year. By modern metrics that may not sound too bad: But remember, inflation had been effectively zero for centuries. What happened?

Like with most historic events, there’s vigorous debate over the root cause. But I am confident it can all be traced back to the “great debasement” of the 1540s when Henry VIII and his advisors took a single gold coin, melted it down, added worthless metal, and then recast two brand new “golden” coins. Essentially, he figured out how to turn lead into gold.

One gold coin became two.

Henry spent the newly created money on wars and palaces, on new wives and parties, or whatever he wanted. As money supply expanded, the demand for “stuff” increased commensurately, and merchants increased prices. This had never happened before.

Seemingly a perfect way to increase capital in the king’s treasury, Henry’s heir – Edward VI – kept to it. Scotland decided to follow suit. And later, an area known as “the southern Lowlands” which is now Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg, followed suit, debasing silver coinage 12 times up to the early 1600s.

If global output – meaning global GDP growth – was increasing commensurately, this might have been tolerable. But it was not.

No, in fact, the world’s economic output was stagnant for more than 1,700 years.

From the time of the Roman Empire – let’s call it “year zero” – thru the early 1700s, global GDP growth was flat. Zero. The global economy was essentially a zero-sum game. Money moved around, but global economic output remained stagnant.

Enter the industrial revolution and its puffing steam engines. The global growth rate SKYROCKETED to 0.5% per year between 1700 and 1820. And by the end of the 19th century, it had reached 1.9%. During the 20th century, according to The Economist magazine, it averaged 2.8% per year. At this rate, global GDP doubles every 25 years.

AI evangelists would have us all believe that AI will accelerate global growth even faster. Detractors suggest this is unlikely.

Once again, we’re back to comments from experts at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, or MIT. Daron Acemoglu, an economic professor at MIT since 1993, estimates that AI will increase global GDP by no more than 1.56% in total over a decade. In his paper “The Simple Macroeconomics of AI” (Economic Policy, 2024), Acemoglu estimates that over the next 10 years AI might boost GDP by 0.93 % to 1.16 % given moderate investment response, and 1.40 % to 1.56 % in a more optimistic investment boom scenario.

Of course, other credible, well-known economists and financial experts disagree. They envision economic growth that is many levels of magnitude larger. Right or wrong, the numbers are compelling: If AI is responsible for another 1.50% annual increase in global GDP, bringing the growth rate to 4.5%, global GDP doubles in 16 years. At a 6% growth rate, doubling will occur in 12 years.

Global GDP is currently about $115 trillion. A doubling brings it to $230 trillion. A staggering figure … but is it even possible? Even if we’re not playing a zero-sum game, aren’t there legitimate guardrails, where any further gains for one segment of society must come at the expense of another? Paul Simon likely said it best with his musical quip, “One man’s ceiling is another man’s floor.”

Ultimately, it all comes down to productivity, which is a measure of “output” per fixed unit of labor time. Most economists believe artificial intelligence will lift labor productivity and thus boost global GDP growth. But by how much?

In a paper titled, “Explosive Growth From AI Automation: A review of the Arguments,” published by ‘Epoch AI’, the authors opine:

“We examine whether substantial AI automation could accelerate global economic growth by about an order of magnitude, akin to the economic growth effects of the Industrial Revolution. We identify three primary drivers for such growth: 1) the scalability of an AI “labor force” restoring a regime of increasing returns to scale, 2) the rapid expansion of an AI labor force, and 3) a massive increase in output from rapid automation occurring over a brief period of time. Against this backdrop, we evaluate nine counterarguments, including regulatory hurdles, production bottlenecks, alignment issues, and the pace of automation. We tentatively assess these arguments, finding most are unlikely deciders. We conclude that explosive growth seems plausible with AI capable of broadly substituting for human labor, but high confidence in this claim seems currently unwarranted. Key questions remain about the intensity of regulatory responses to AI, physical bottlenecks in production, the economic value of superhuman abilities, and the rate at which AI automation could occur.”

The Epoch AI paper frames “explosive growth” as growth far beyond the historical range — in other words, not 3–4% a year, but 30%, 50%, or even higher annual GDP growth. At this kind of growth rate, the global economy could double in size in a few months or even weeks, not decades or years. The foundation of this argument is this: If a single AI researcher is as productive as, say, 1,000 humans, and that researcher can “spin up” 10,000 copies in the cloud, math suggests we’ve effectively created a new labor force of 10 million PhD-equivalents overnight. This means the “capital creation bottleneck” of human capital is bypassed.

Hmmm ….

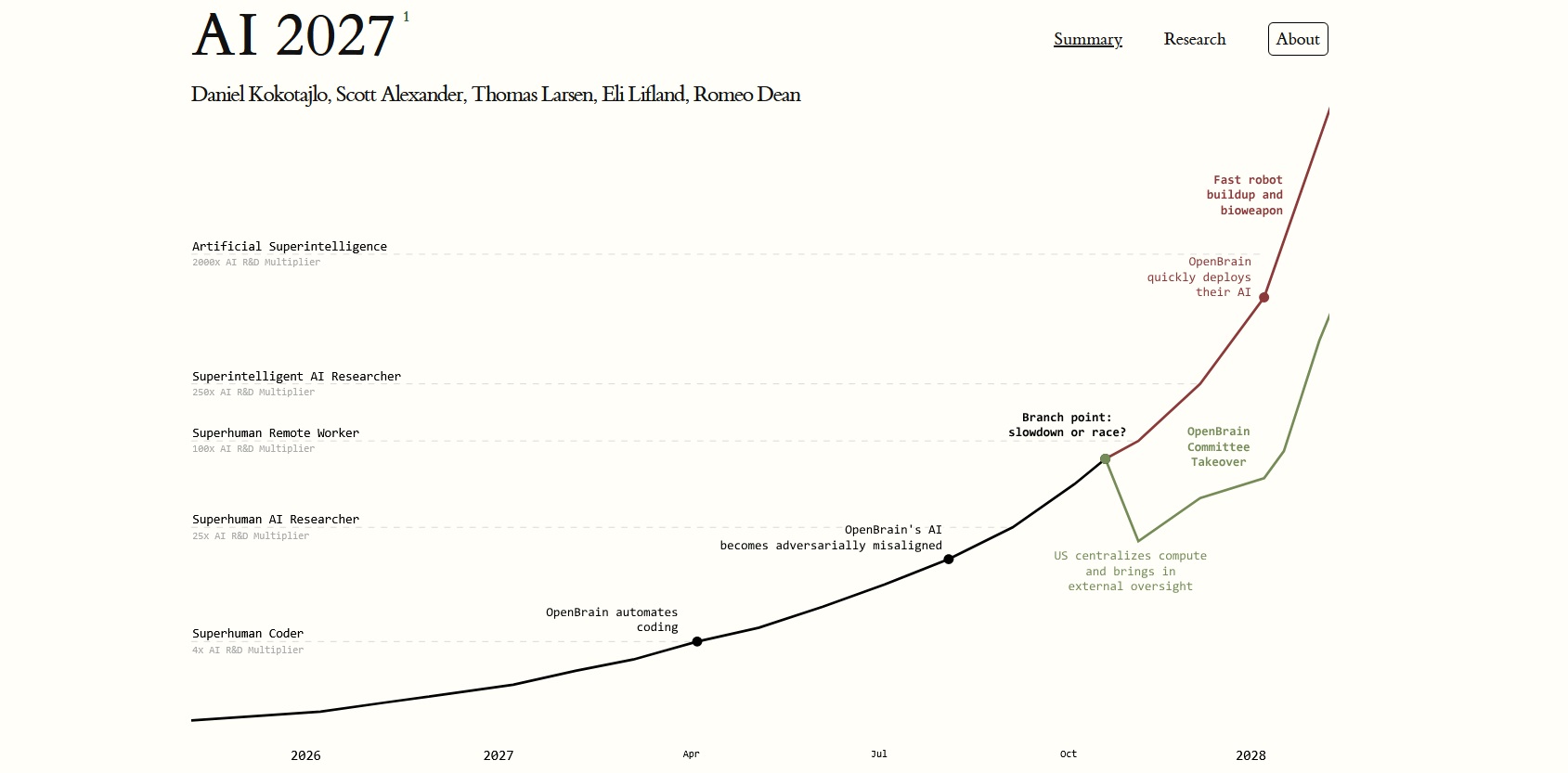

Daniel Kokotajlo is the Executive Director of a non-profit research organization called the “AI Futures Project.” He previously worked at OpenAI. Daniel and his team recently released a research piece titled “AI 2027.” By early in 2027, they expect some amazing things to happen:

In March of 2027, they forecast a “superhuman coder milestone” will be reached. What does that mean? A “superhuman coder milestone” – let’s call this the SCM – describes the point at which an AI system can write computer code better than the best human programmers. The AI Futures Project, OpenAI, and others believe this is the precursor to achieving “Artificial General Intelligence”, or AGI.

If this were to occur, experts expect a massive productivity boost, as – in theory – all barriers to innovation are eliminated. In this SCM theory, AI can code itself, which in turn becomes even better AI code, and so on. Presumably instantaneously?

It’s hard to fathom. And, of course, it’s hard not to think that SCM won’t sheppard in the end of humanity, a la ‘The Terminator.’

Skynet? Are you listening?

But assuming we don’t all die instantaneously from global nuclear war, the questions remain: Is AI truly economically transformative? Will global GDP growth increase exponentially? Will GDP per capita rise in tandem, paving the way for a ‘universal basic income’ sizable enough to where “work” becomes optional?

Or is this whole thing a bubble?

Or perhaps this issue is not binary? Perhaps the right answer is the current state is neither an economic skyrocket nor a financial sinkhole, but something in between? Could it be that the massive AI capital expenditures by the hyperscalers might end up paying off handsomely, but not as extensively as they expect?

Here’s an AI 2027 link if you want to dig deeper:

https://ai-2027.com/research/takeoff-forecast

In September, on Meta’s Access podcast, Mark Zuckerberg said an AI bubble is “quite possible.” But he added that his bigger worry is not investing enough and falling behind if AI advances rapidly. “If we end up misspending a couple of hundred billion dollars … I actually think the risk is higher on the other side.” His logic: if superintelligence or transformative AI breakthroughs come sooner than expected, being too slow means you lose your competitive position, influence, and can’t catch up.

To me, it appears Zuckerberg is thinking of this problem somewhat like the classic game-theory problem called the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Look it up using your favorite AI engine! 🙂

But on the “good news” side of the ledger, Meta and the others can afford it. Amazingly enough, they can each afford to lose a couple hundred billion dollars without impacting their legacy businesses. So the bigger risk, their behavior suggests, is coming in last. Clearly, Zuckerberg believes that is not an option.

Companies during the dot-com frenzy soaked up massive amounts of investor capital. Absurd valuation metrics such as “eyeballs” – website traffic – as opposed to revenue or profit were touted as most critical. Seriously flawed business models were everywhere.

I suspect some aspects of this will repeat within the massive AI infrastructure build-out. Billions are likely to be invested into any startup with the letters AI in their name or business plan. Many will likely fail.

But there are some key differences in the current frenzy. The exceptionally size and stability of the hyperscalers is the biggest. Most of the “Magnificent Seven” are mature, exceptionally profitable businesses whos’ earnings and value made up a significant portion of the S&P 500 before the AI investment boom began. These firms have huge revenue streams and are sitting on large stockpiles of cash. Even after all their CapEx spending.

In the final analysis, I think the “bubble” debate should be viewed thru a somewhat tangential lens, a variant of binary ‘yes/no’ choice. Let me explain.

I began today’s blog sharing the fact that since the year 1AD, and continuing for 17 centuries thereafter, the world’s economic output was flat. There was no growth in output; any gains one group realized generally came at the expense of another. The global economy was essentially a zero-sum game. The Romans conquered many other groups, and then pirated that civilization’s gold, jewelry and religious objects. Land was taken and redistributed to Roman citizens; often, conquered people were enslaved. Nothing new was created; value only shifted from one group to another.

Everything changed – economically speaking – with the industrial revolution. By the 20th century, global GDP growth averaged 2.8% per year. AI evangelists believe that AI will accelerate global growth even faster.

Are annual global GDP growth rates of 10%, 20% … 100% even possible?

Certainly not, I would opine, within the traditional or historic models of value creation wherein some combination of human labor, capital, innovation and technology combine to increase productivity. GDP growth generally requires some amount of all these components.

Clearly, the labor force isn’t going to double next year. Nor will global capital. So the only plausible lever is technology. That is the only factor that might theoretically sustain a 100% growth rate in global GDP. Theoretically. But is this concept only economic science fiction? Is it even possible in the real world?

The massive, multi-trillion-dollar investment in global AI facilities and technology is real. The money is being spent. Globally. Every dollar spent increases overall global economic activity – probably by about 5X. So this activity, in and of itself, is creating economic growth. But will it ultimately create new value? Beyond the “boom” created by the CapEx itself? That’s the trillion-dollar question. And it’s a question we simply cannot answer today. We can only opine.

Hoping to gain one more opinion, I interviewed a well-known “technologist.” This person opined that 2025 definitely “feels like” the late-1990s. His comments included a belief that the infrastructure build was massive and excessive then – much like today – and he commented “billions were lit on fire” before the ‘bust’ occurred.

He wondered aloud “what has to be true” in order to rationalize the trillions allocated to AI infrastructure? A good question. But asked the question, “Is there something here?” his answer was, “Of course. This is transformational.”

The Dallas FED seems to agree. Sort of. In a paper published a few months ago, titled “Advances in AI will boost productivity, living standards over time”, and the paper begins with these comments:

“Artificial intelligence (AI), like many technologies before it, offers the potential to improve people’s living standards. Such advances can be approximated by changes in gross domestic product (GDP) per capita over time—the rate of change in the amount of output per person.

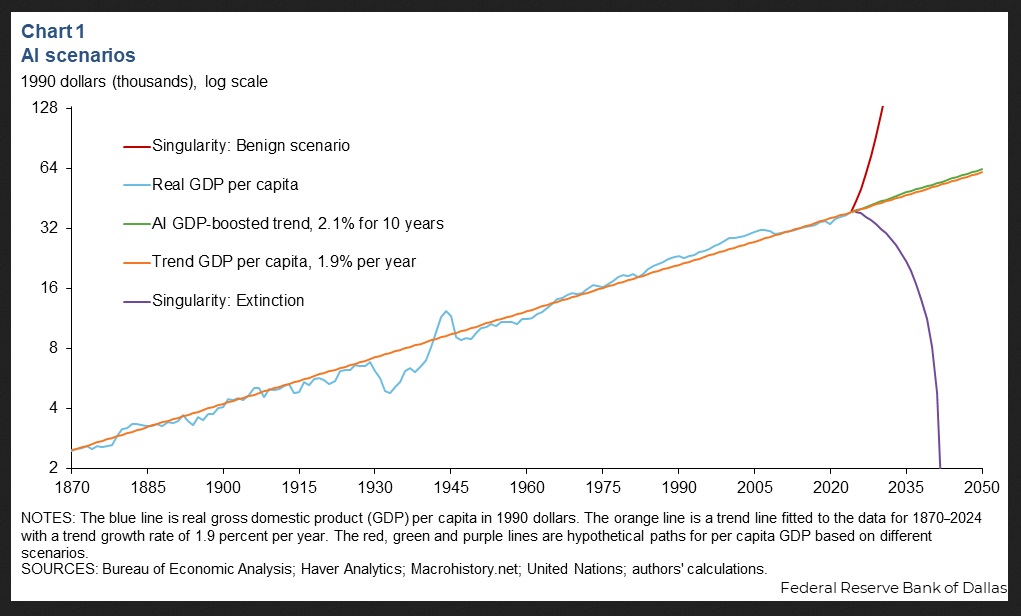

Chart 1 shows GDP per capita from 1870 to 2024 along with scenarios, some of them extreme, depicting what could happen to living standards between now and 2050.”

They followed up with this image:

As you can see in the “notes” the red and purple are “hypothetical” paths. In the red path, GDP per capita effectively goes straight up. Everyone is rich! In the purple path, everyone apparently becomes unemployed once “singularity” or AGI is achieved. Is this the scenario where machines take over and kill us all?

Yep. That’s what the Dallas FED paper is suggesting: “Under a less benign version of this scenario, machine intelligence overtakes human intelligence at some finite point in the near future, the machines become malevolent, and this eventually leads to human extinction. This is a recurring theme in science fiction, but scientists working in the field take it seriously enough to call for guidelines for AI development. Under this scenario, the future could look something like the (hypothetical) purple line in Chart 1.”

Of course, this is nothing we haven’t heard before. It’s just the source that’s rather unusual. One doesn’t expect such comments from the FED. 🙂

Finally, in the “bubble talk” discussion it’s worth mentioning an often forgotten “bubble” in the early 2000s. Do you recall the commodities “Supercycle” that grew out of the Dot-Com bust? This is mostly forgotten … but in the early 2000s, China joined the WTO and began an era of super rapid industrialization, like a sponge soaking up global commodity supplies to fuel their expansion. As their demand accelerated against a relatively static global supply, commodity prices exploded. In 2002, the per-barrel price for oil was about $20. By 2008, that price was $147. Copper prices exploded from $0.60 a pound in 2001 to about $4/pound in 2008. Iron ore, soybeans and corn all reached new highs. Mining and energy companies all experienced massive interest and investment.

It all collapsed with the Great Recession of 2008. That’s what a global financial crisis will do. It’s worth noting that China’s industrialization continued and a year or two after the financial crisis receded, commodity prices rebounded somewhat. Is today’s AI push similar? There are definitely some similarities.

Coming full circle today, consider the title of today’s blog: “Zero Sum Game?” Thru my research and interviews on this topic, one outcome most folks seem to agree upon is this: The massive allocation of society’s resources to AI infrastructure will be transformational. The world is changing. Our challenge, of course, is we’re not certain how. But everyone seems to agree that change is in the air. There will be winners and losers; and Meta, as Mark Zuckerberg has made patently clear, wants to be one of the super winners when all the dust settles.

And if the AI “game” is a zero-sum game, where the winners can only win if the losers lose, who will be the losers?

Historically, thru periods of prior industrial and technological advances, as GDP advanced and grew, and corporate profits rose, labor was the loser.

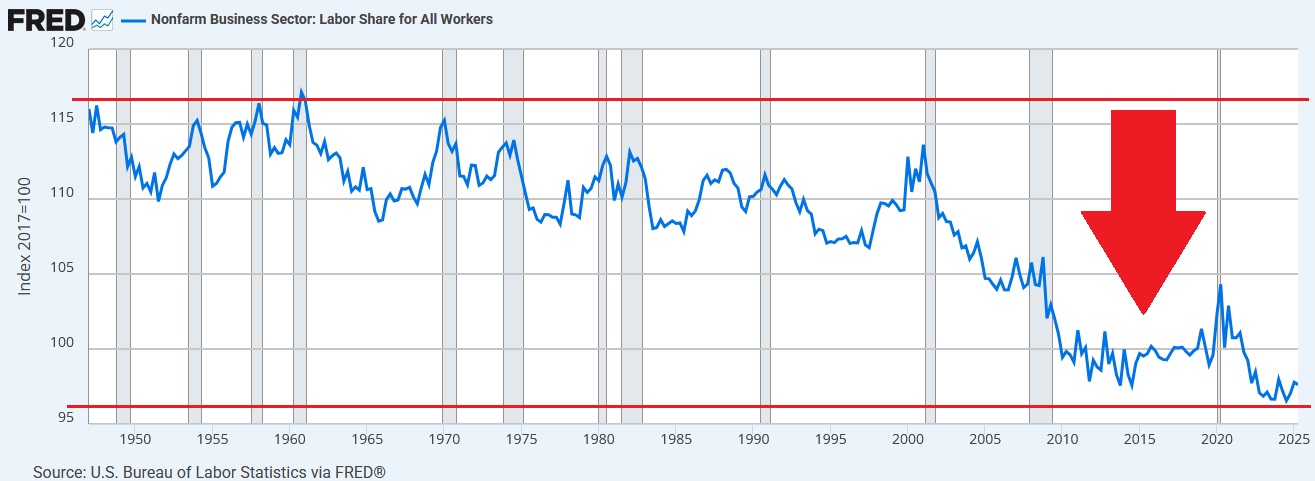

The image below is from FRED – The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. It tracks the “Labor Share” as a percentage of output – essentially GDP – from 1947 thru 2025. Thus, the chart below captures the time period beginning right as WWII ended, and America was at full industrial strength, thru the birth of the technological revolution: The creation and growth of the microprocessor, the birth of the computer, the internet, etc.

The chart itself is an index. 2017 = 100. This is not an overly meaningful point, but it is important for context. Take a look:

“Labor Share” is defined as the portion of total output that goes to labor compensation (wages, salaries, and benefits), as opposed to capital (profits, rents, depreciation).

Thus, the formula is:

So supposing the Labor Share is 60%, that means 60 cents of every dollar of value created in the nonfarm business sector is paid to the workers, while 40 cents goes to capital owners.

In the early years, say from 1947 thru 2000, the Labor Share of output was relatively consistent. But it dropped thru the floor at the turn of the century, and has continued to decline year after year?

Why? Advances and improvements in technology have consistently eroded the need for labor to generate output. My concern – and that of many other financial and economic experts – is that trend will continue, and likely accelerate, as AI expands its reach and implementation.

In other words, it appears likely to me that if this is a zero-sum game, or at least partially so, the labor force is likely to take it on the chin. While, concurrently, American businesses increase their profitability. Of course, this will be a great outcome for the investor class — stockholders — but extremely bad for the working class. Sorry, but I give this outcome a high probability. It seems almost inevitable to me. The bigger questions, in my mind, are: One, how future global society grapple with this issue.

And two, will economic and financial AI gains come at the expense of another, less fortunate, group? Or can GDP per capita truly rise to the heavens as AI integration, and overall output, expands?

On that somewhat depressing note, let’s grab a bottle of wine and head to the steakhouses.

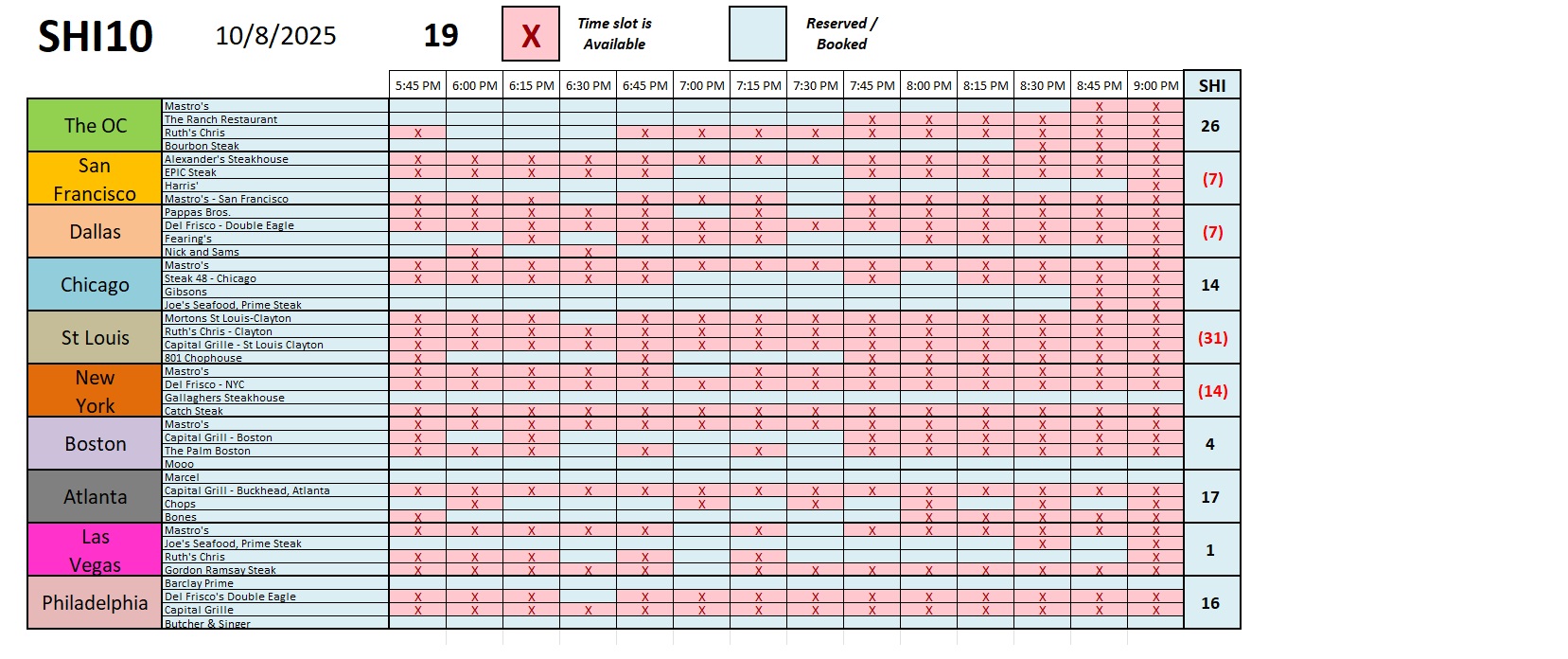

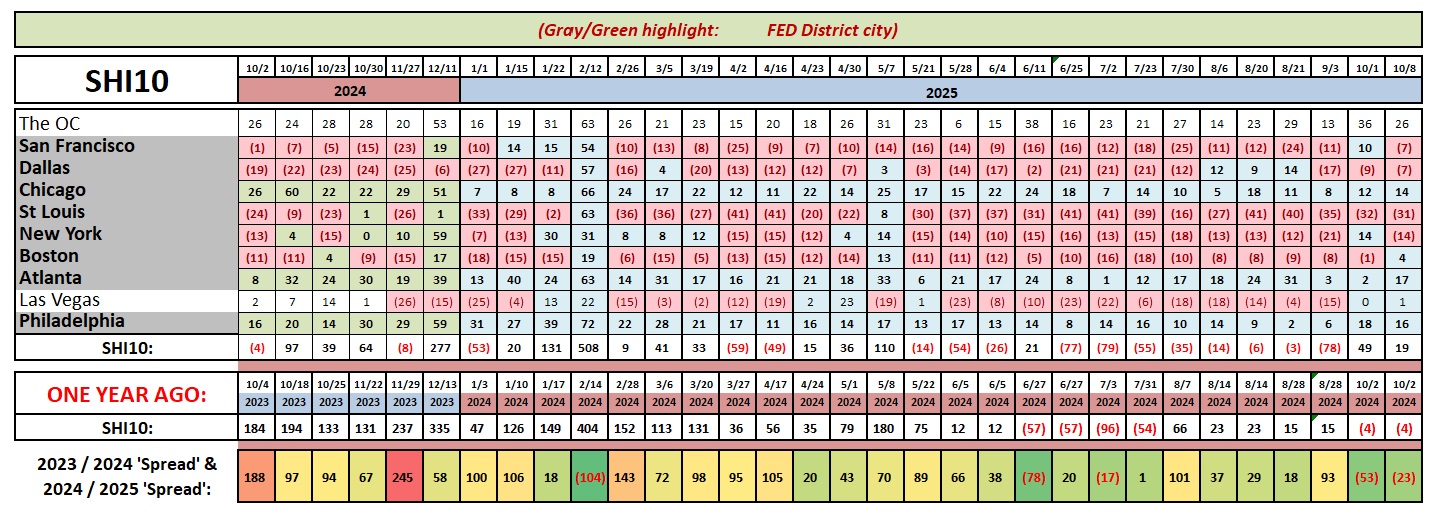

The SHI40 managed to squeak out another positive reading today. The individual SHI cities all seem to be maintaining relatively stable expensive eatery reservation demand. Demand in ‘Vegas remained positive for the second week in a row.

High level, the SHI40 continues to reflect general economic stability, albeit at a lower level than a year ago. Reservation demand seemingly fell off a cliff in the second half of 2024 before plateauing at current levels. There’s not much we can take away from these stable, lukewarm figures, economically speaking, except this: Things aren’t bad in the expensive eatery business! They’re not great … but not bad. 🙂

I’ll wrap today’s discussion with a bit more comment around one of the more famous “bubbles” that many of us experienced personally — the Dot-Com bust.

In 1996, the then-Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Alan Greenspan, gave a historic speech to a business group in Washington DC in which he said, “… But how do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values, which then become subject to unexpected and prolonged contractions as they have in Japan over the past decade?”