Global Debt Mysteries

“Nowcasting” the GDP

May 20, 2016The French are Revolting!

May 23, 2016“High debt forces interest rates to stay low, which encourages yet more debt…” says Manor Pradhan, an economist at Morgan Stanley, talking about the massive increase – globally – in ‘gross general government debt.’ An interesting statement.

And a thought provoking one as well. Essentially, does the dog wag the tail? … or does the tail wag the dog? Do higher debt levels force rates lower … or do lower interest rates drive debt levels higher? Or are they unrelated all together?

Why you should care: Ironically, here in the aftermath of the ‘Great Recession,’ developed nation government debt levels (in both absolute terms and as a percentage of GDP) have never been higher. Sure, we saw huge spikes in debt levels during the major wars of the 20th century, but never before have so many countries owed so much to so many. This time it is different.

Taking action: Are you getting a loan? Should you borrow on a fixed rate, or a variable rate? And if variable, what index should you tie to your margin? As global interest rates will stay very low (by historic standards) for a very long time – perhaps permanently – I suggest a variable rate is your best bet.

THE BLOG: At these lofty debt levels, Pradhan believes that central bankers will not push up rates too quickly, for fear of a new financial crisis. I believe he’s right. But there is another reason why the FED and other central banks will neither push up rates too quickly nor will they raise them much at all: Interest expense. Say what you want about deficit spending, developed nation intelligentsia know it’s neither popular nor sustainable. As interest rates rise, so do deficits.

Sure, if a nation can borrow at zero, indefinitely, interest expense is irrelevant. But at anything other than zero, rates matter.

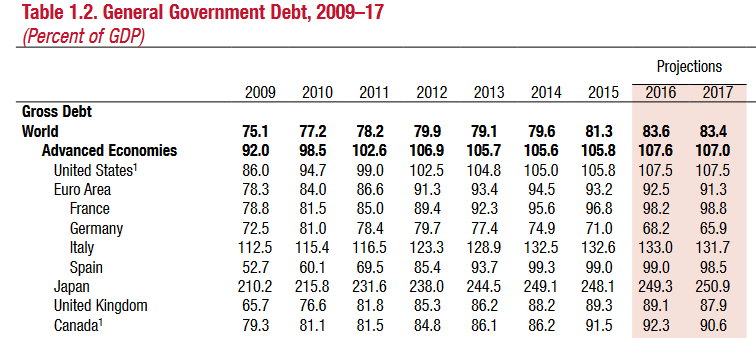

The Great Recession took a massive toll. The figure below, provided by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) shows how much. In each of the five prior analyses – between 2007 and April of 2016 – as a percentage of GDP, gross government debt increased both in absolute terms and in forecast (dotted lines).

Clearly, this graph shows a disturbing trajectory. Assuming interest rates are anything other than zero, government debt service is problematic. Even assuming steady interest rates – like those we’ve seen in the past 5 or 6 years – increased debt levels demand increased interest payments.

Unless interest rates are zero. Which they are, today, for some nations. But not the US.

Here’s a bit more data to consider:

Take a look at the ‘Advanced Economies’ above. As a percentage of GDP, US government debt is up 24% between 2009 and 2015. The EU…about 20%. The UK debt has grown by over 36%, Canada by only 15%, and Japan by 18% – to almost 2.5X their annual GDP!

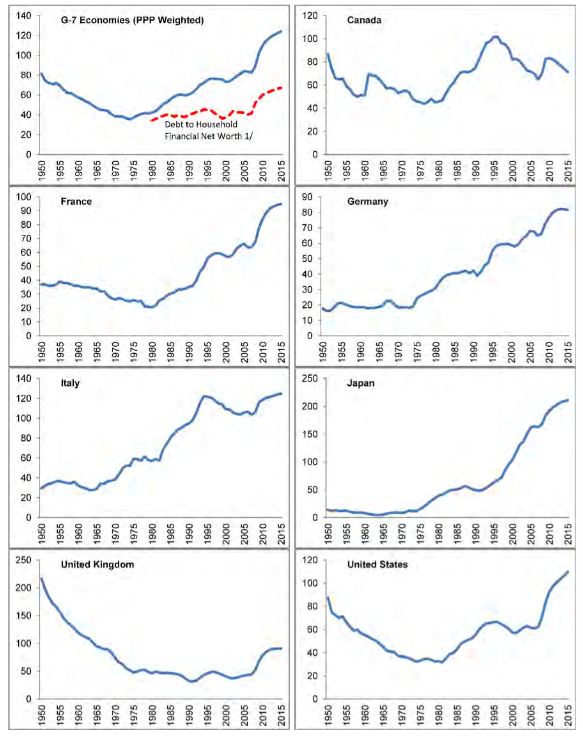

Perhaps this doesn’t seem to bad to you … until you consider the years before 2009. From an earlier IMF report, I found this chart entitled “General Government Gross Debt in G-7 Economies, 1950-2015 (In percent of GDP)“:

So back to our question, which wags which? The tail or the dog? I would suggest reality is a little of each. Depending on the size of the dog and the size of the tail.

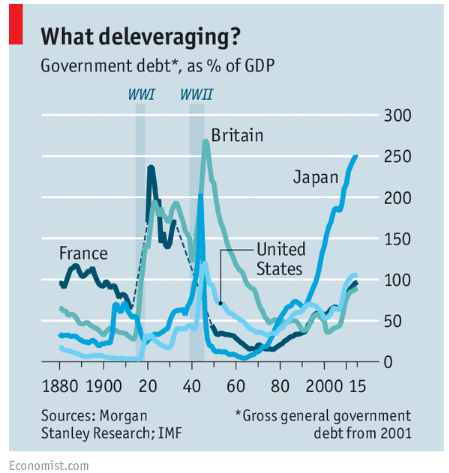

And central banks know this. They know they face a new challenge today. Here’s an interesting question: Can we ‘grow’ our way out of it? Meaning if GDP were to grow at, say, 5-6% per year for quite a while that would have the effect of significantly reducing the debt/GDP ratio. Here’s a great chart from the Economist magazine showing how this was accomplished in the past:

Post WWII GDP growth was very effective in reducing the US debt/GDP ratio. In 1945, the ratio was higher than it is today.

So all we need is massive annual GDP growth, for a few decades, and we’re out of the woods right? Right. You know my feelings on this topic. This is as likely as Donald Trump becoming the US President! What? You say he might? Hmmm….

I’m joking of course. There’s a greater chance of a Trump presidency than of 5+% GDP growth over the next decade. Whether Trump is President or not.

From their article, “a chronic problem” printed on May 14th, they share some Morgan Stanley thoughts on reducing the debt burden:

- “One would be to replace (government) debt with equity-like capital. (If a bond’s repayment value is linked to real GDP, then governments would be spared the crippling surge in debt-to-GDP ratios that occurs during recessions.)

- In the private sector, equalizing the tax treatment of equity and debt would be a good idea, although tricky to implement. (Creating “shared-responsibility mortgages”, in which lenders take an equity stake in the homes they finance, would make borrowers less vulnerable to house-price declines.)”

The article suggested these seem sensible – I don’t. They seem irrational. I can’t imagine why buyer of government would agree to the first, nor why banks would agree to the second.

No, we’re stuck with debt that requires interest payments. The global agencies responsible for financial management know that. And at these debt levels, unless we see a huge, sustained spike in GDP – across the globe – they have to deal with it.

By moving rates slowly … by moving rates gradually … and by not moving them much.

- Terry Liebman

2 Comments

Good one.. Thx

Sent from my iPhone

I do believe all of the ideas you’ve offered in your post. They are very convincing and can definitely work. Nonetheless, the posts are very brief for beginners. Could you please lengthen them a bit from next time? Thanks for the post.