Savings UP … while Rates are DOWN? What’s UP with that?

The Steakhouse Index Update – 8/24/16

August 24, 2016Steak House Index Update 8/31/16

August 31, 2016Many years ago, there was a time when Americans saved quite a bit of their income for that proverbial rainy day. And for retirement.

When the BEA began keeping records in 1959, the US ‘personal savings rate‘ was about 11% of gross income. And it stayed between 10% and 12% until the early 80s.

Then, for some unknown reason, it fell precipitously. It bottomed at a paltry 1.9% in 2005. That is a massive decline. If that trend continued thru today, the US savings rate would likely be less than zero – much like the negative interest rates around the globe.

Yet, the opposite is true. In December of 2012, once again, the savings rate topped 11%. Why? What’s driving this behavior? And why should we care?

Why You Should Care: Beyond the intellectual quandary, if this American behavioral change is highly correlated with, and the result of, our super low long-term interest rates, then this is VERY important. Why?

Here’s the definition of ‘disposable income‘: “Disposable income is that portion of income remaining after deduction of taxes and other mandatory charges, available to be spent or saved as one wishes.”

So, after paying for the necessities – food, shelter, clothing, and taxes – our remaining funds qualify as disposable income. Which can be saved or spent.

If it’s spent, it drives economic growth. Remember: Consumer spending is the foundation of our economy…the source of the majority of economic growth.

But if it’s saved, it doesn’t help the economy one bit. Thus, an increased US savings rate actually harms the economy by shrinking GDP growth!

Taking Action: Read the blog below. Once again, if you agree with my conclusions, regardless of what we see in the news, glean from media, read on the internet, etc, we have to remain steadfast in our belief: Our long-term interest rates will remain lower for longer and investment asset prices will continue to rise. Make decisions and act according.

The BLOG: Andy Haldane is the Chief Economist of the Bank of England. In 2014, Time magazine named him one of the 100 most influential people in the world. Impressive.

Recently, Andy opined that global interest rates are now, “lower than at any time in the past 5,000 years.” I have no doubt he’s correct. And like many central bankers and economists, he’s concerned about the longer term effects of zero- and negative-rate debt. And while central banks have tools to manage this negative rate environment, at present they have none to effectively force negative rates on savings and currency in circulation:

“The need for unconventional measures arose from a technological constraint – the inability to set negative interest rates on currency.

It is possible to set negative rates on bank reserves – indeed, a number of countries recently have done so. But without the ability to do so on currency, there is an incentive to switch to currency whenever interest rates on reserves turn negative. That hinders the effectiveness of monetary policy and is known as the “Zero Lower Bound” – or ZLB – problem.”

Said another way, if a central bank charges their ‘customers’ a fee to hold their money, their customers may simply convert those deposits into currency. Thereby avoiding the fee.

In a recent speech, he suggested one possible solution: We need to “…find a technological means either of levying a negative interest rate on currency, or of breaking the constraint physical currency imposes on setting such a rate.

More recently, a number of modern-day variants of the stamp tax on currency have been proposed – for example, by randomly invalidating banknotes by serial number.”

What? Randomly making currency worthless? Could they?

Imagine if they did. For the first time in ages, you pull out that $100 bill – you know, the “emergency” bill you’ve had in your wallet for quite a while – only to discover that banknote was, oops, voided? OOPS.

OK, I’ll agree, this is a rather dystopian future view. But if excess savings ARE the result of super-low long-term interest rates, resulting in further GDP declines resulting from lower consumer spending, how might the government motivate us all to spend more and save less? Simple: Randomly void currency in circulation by serial number. And require banks to charge a fee to hold checking and/or savings accounts.

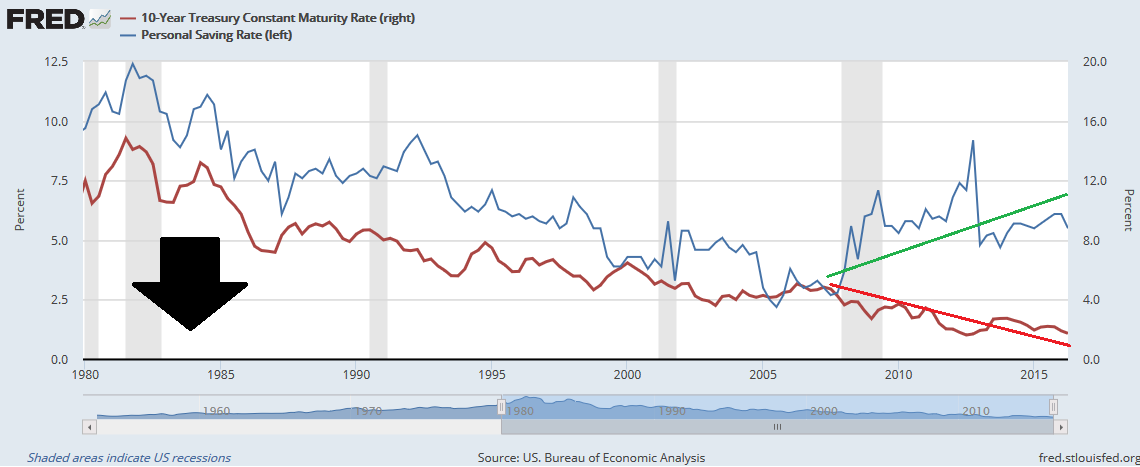

Because here’s the problem. Take a look at the chart below:

Look at the near perfect correlation between savings and the 10-year CMT. Until around 2008. When they began to diverge. (See the green and red lines.)

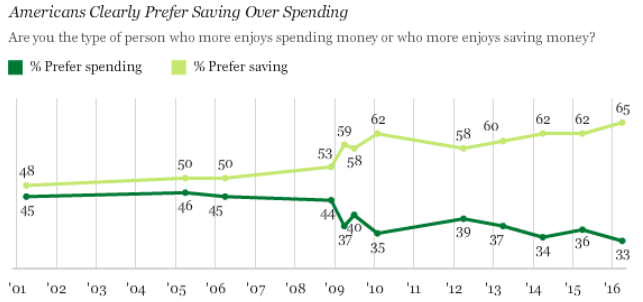

In April, Gallup released an article highlighting this issue. Entitled, “Nearly Two-Thirds of Americans Prefer Savings to Spending” the article posted this graphic:

…and commented, “the gap between those who prefer saving and those who prefer spending is at its widest since Gallup first asked the question in 2001.”

(Here’s the link if you wish to read the article: http://www.gallup.com/poll/190952/nearly-two-thirds-americans-prefer-saving-spending.aspx)

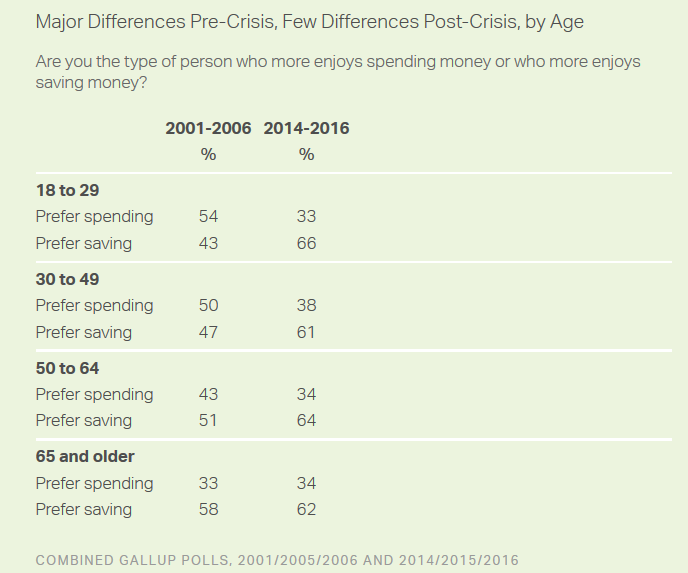

Interestingly, I thought the greatest increase in the “prefer saving” camp would have been in the older folks. Not true:

Younger folks are far more interested in saving more than their older counterparts.

If consumer spending drives GDP growth … and those most likely to earn and spend significantly increase their savings … then we may have a problem.

Ultimately, I suspect the increased US savings rate has been impacted by both demographics and perception. The longer we experience interest rates at these historically low rates, I suspect younger folks, more concerned about their “nest egg in retirement,” will save more. They probably feel can’t rely on ROI growth to keep them comfortable in retirement. They apparently feel they need more savings.

Unfortunately, as we’ve discussed int he past, the US has an economy heavily reliant on consumer spending. Personal savings is money not spent – it’s saved. Thus savings and consumer spending are diametrically opposed.

Once again, we find another challenge facing GDP growth.

- Terry Liebman