The Physics of Economics, Part 2

SHI Update – June 8, 2016

June 8, 2016The Greater Fool Theory

June 14, 2016This blog is the second in a series of 3. Here is the link to number 1:

The Physics of Economics – Part 1

Sir Issac Newton is known as one of the most influential scientists of all time. In the second half of the 17th century (and into the 18th), Newton was one of a number of ‘Natural Philosophers’ who sought to explain natural phenomenon using math and physics (among other things.) His 3 ‘laws of motion’ have become the foundation upon which centuries of classical mechanics (physics) are based…

Why you should care: Not only do Newton’s 3 laws explain – and predict – behaviors of the physical bodies all around us, I believe they also can be applied to, and explain, global financial market behaviors. They can help explain how current expectations modify human behavior. And they can help us understand (and predict) both the persistence of large market trends and the concept of ‘unintended consequences.’

Thus, knowing the 3 laws, and how to apply them, might us predict future market behaviors and directions.

Taking action: Apply the logic … test my theories. See if they help you gain insight. Perhaps they will help you forecast future economic outcomes that may impact you personally.

THE BLOG: In the first blog, I suggested the below summarize Newton’s 3 laws of motion:

- Law 1: “An object traveling at a constant speed, in a constant direction, will continue to do so unless acted upon by another force.”

- Law 2: “Force = Mass times Acceleration” (F=M*A)

- Law 3: “For every action there is an equal, yet opposite, reaction.”

Law 2, in its simplest form, suggests two corollaries: First, the bigger an object (event), the more force it takes to move it in a different (or new) direction. Second, the larger an object (event) is, the greater its ability to impact (affect) nearby objects (conditions).

In other words, Law 2 suggests the gravitational pull of an economic event is directly correlated with it size.

There is no larger ‘economic event’ than energy. Price movements impact every human, business and government on the planet. Which means we must do all we can to understand it – as best we can – and understand the implications of changes impacting this market.

Here is an ‘inflation adjusted’ chart of WTI crude back to 1946. (I’ve added the red lines to show approximate ‘average’ price plateaus for emphasis.)

Remember, these are inflation adjusted numbers. Values are adjusted to equal today’s dollar value. Without adjustment, ‘nominal’ historic WTI prices for the same period look like this:

By either measure, oil prices in the past ten or so years have been very high by historic standards. Which meant oil-exporting countries were enjoying a financial bounty of unprecedented proportions.

That is until May of 2014 when global oil prices plummeted. Bottoming in January of 2016 at $26.55.

Now, in the middle of 2016, with oil prices hovering near $50, as supply and demand forces continually ebb and flow in some semblance of equilibrium, we have to consider what the recent price moves suggest about the future.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) addressed just this issue in their published report entitled “Learning to Live with Cheaper Oil”. Here is the link to the 52 page report if you’re interested:

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/dp/2016/mcd1603.pdf

From that report: “Over the past 15 years, …oil exporters enjoyed large external and fiscal surpluses and rapid economic expansion on the back of booming oil prices…. However, as oil prices have plunged by some 60 percent since the middle of 2014, fiscal and external surpluses have turned into deficits and growth has slowed, raising concerns about unemployment and financial sector risks.”

And they asked this question, “How should the exporters adjust to the new oil market reality?”

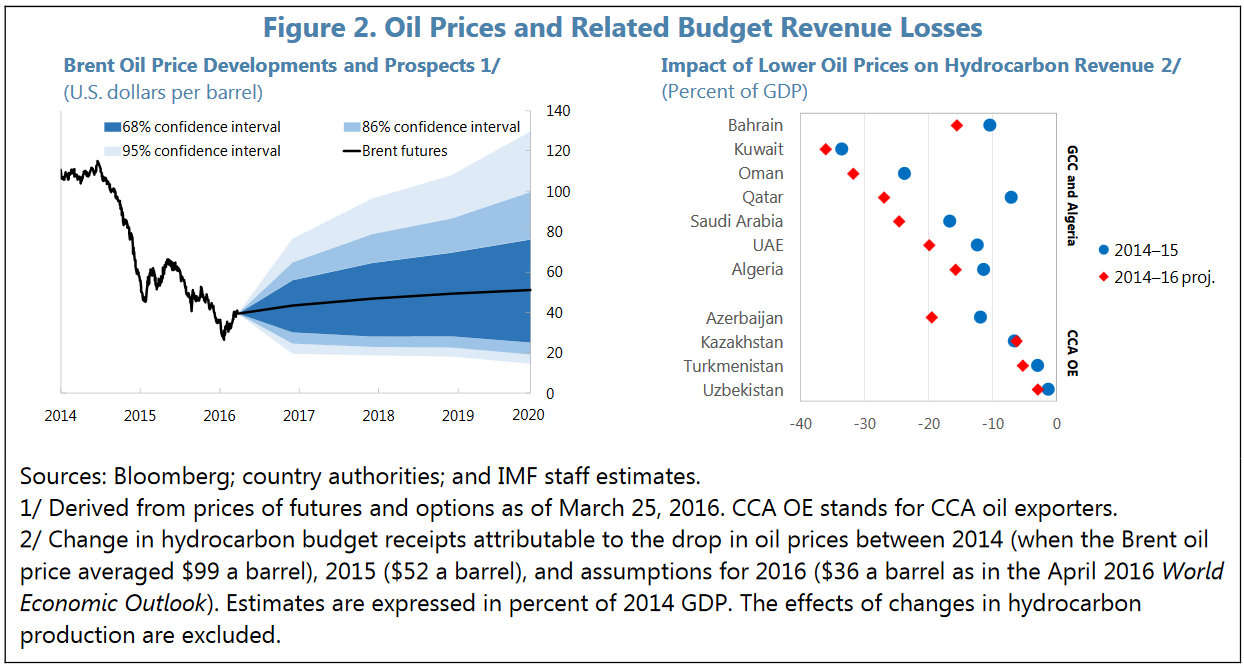

Of course, no one can accurately predict oil next week let alone 2020. However, the IMF has a fairly robust data set upon which to rely…and they’re made this prediction (click to enlarge) for Brent Oil prices:

On the right side you can see the adverse impact on middle east countries is massive. Annual surpluses have swung to huge double-digit revenue deficits.

Assuming the Brent futures and the “68% confidence interval” (see above) are relatively accurate, the above question has merit. Assuming their forecast is accurate, the IMF expects cumulative budget deficits in the OECs are expected to exceed $1 trillion in the next five years.

This is a monumental issue. And the resulting questions/implications for each of oil-exporting countries (OEC) – and the rest of the world – are equally monumental. Because each question below has its own corollary question: How does the answer impact/affect other markets and countries around the globe?

- With annual revenue deficits of 20% or more of their GDP – each year – how can these countries adapt to the new paradigm?

- Should each OEC focus more on spending cuts, generating non-oil revenue, or changing their internal tax structures?

- In the interim, should the OECs, if possible, enter the global debt markets? If they do, should they borrow in US dollars (USD) or in their own currency?

- Should a country like Saudi Arabia maintain its currency ‘peg’ to the USD, unlike the Russian Ruble which floats in the foreign exchange market?

- How much will spending cuts reduce GDPs in OEC countries?

Let’s take a look at the implications of a few economic questions from above. Suppose Saudi Arabia decided to ‘un-peg’ the Saudi Riyal from the USD. And suppose further the Riyal depreciated 50% against the USD. The immediate impact: Their local currency (Riyal) revenue from oil sales (which occur in USD) doubles overnight. That could go a long way to solving their revenue problems within the country.

But it has other implications. Any debt they owe, in USD, now cost twice as much to repay. Every US import (and the rest of the world, possibly, depending on currency relationships) now costs about double what it use to. If wages were to rise, in compensation for reduced purchasing power (foreign goods), inflation within the country could spike to undesirable levels.

What impact will reduced spending and reduced GDP growth have on job growth and unemployment within the OEC in and around the middle east?

Per the IMF, low growth will push up unemployment in the middle east region. The United Nations estimates 3.8 million people will enter the gulf coast OEC labor markets in the next 5 years, with 1.3 million unemployed. Including all nations in the region, the IMF estimates the numbers could be 10 million new job seekers with 3 million unable to find a job.

Which, of course, raise non-economic questions:

- What might happen to global terrorism in light of falling revenues in the OEC?

- What impact might these issues have on regional geopolitical stability?

As time passes, and facts become known, its easy to see this issue – and the resultant implications – are massive. We will continue to follow and see how it unfolds.

- Terry Liebman

1 Comment

[…] https://terryliebman.wordpress.com/2016/06/12/the-physics-of-economics-part-2/ […]