SHI 3.28.18 History Repeats

SHI 3.21.18 FED Day: Following the Script

March 21, 2018

SHI 4.4.18 Brevity is the Soul of Wit

April 4, 2018

History repeats.

Let me apologize right up front: This is a lengthy BLOG post. For this reason, I’m going to summarize my points below … and if you have the time and are feeling spry, go ahead and tackle the entire post. I think you’ll be happy you did.

Last week I picked up, and began reading, “Principals” by Ray Dalio. If you’re not familiar with Ray, ‘google’ his name and you’ll discover he is the founder of Bridgewater Associates, one of the richest people on the planet, and considered by many to be one of the most influential. By any measure, he’s an impressive man.

The book is worth a read. Not only is it well written, but it’s well constructed. Meaning, in my opinion, the reader can act on the information and the ‘teachings’ contained therein. There are lessons to be learned here … the easy, less painful way. I’ll talk more about this below.

For now, here are my very high-level summary points:

- History often repeats itself. If the conditions that generated a specific outcome reoccur, it is possible the same outcome — or one very similar in nature — will occur.

- The Vietnam War was expensive. America paid the cost by increasing money supply by over 50% between 1960 and 1970. The USD was pegged to $35 gold and currency exchange rates between countries were fixed. The effect: US the inflation rate rose to about 6% by 1970.

- The outcome: In 1971, the US defaulted on a global financial commitment, triggering the end of the gold standard, the beginning of floating exchange rates, and the devaluation of the dollar.

The Trump Administration has made some bold moves. One of the goals of the tax cut was to eliminate international tax inequities for our US companies. This was a worthy goal…and one I hope we achieved. One of the goals of the tough trade talk is to level the international trade playing field — and increase demand for US exports. Again, a worthy goal.

But we must consider the unintended consequences of both moves … and their long-term implications.

Welcome to this week’s Steak House Index update.

If you are new to my blog, or you need a refresher on the SHI10, or its objective and methodology, I suggest you open and read the original BLOG: https://www.steakhouseindex.com/move-over-big-mac-index-here-comes-the-steak-house-index/

Why You Should Care: The US economy and US dollar are the bedrock of the world’s economy. This has been the case for decades … and will continue to be true for years to come.

Is the US economy expanding or contracting?

According to the IMF (the ‘International Monetary Fund’), the world’s annual GDP is almost $80 trillion today.

During the calendar year 2017, US nominal GDP increased by $833 billion … by an amount approximately equal to the market capitalization of Apple. At the end of 2017, US ‘current dollar’ GDP was almost $20 trillion — about 25% of the global total. Other than China — a distant second at around $11 trillion — no other country is close.

The objective of the SHI10 and this blog is simple: To predict US GDP movement ahead of official economic releases — an important objective since BEA (the ‘Bureau of Economic Analysis’) gross domestic product data is outdated the day it’s released.

Historically, ‘personal consumption expenditures,’ or PCE, has been the largest component of US GDP growth — typically about 2/3 of all GDP growth. In fact, the majority of all GDP increases (or declines) usually results from (increases or decreases in) consumer spending. Consumer spending is clearly a critical financial metric. In all likelihood, the most important financial metric.

The Steak House Index focuses right here … on the “consumer spending” metric. I intend the SHI10 is to be predictive, anticipating where the economy is going – not where it’s been.

Taking action: Keep up with this weekly BLOG update. Not only will we cover the SHI and SHI10, but we’ll explore related items of economic importance.

If the SHI10 index moves appreciably -– either showing massive improvement or significant declines –- indicating growing economic strength or a potential recession, we’ll discuss possible actions at that time.

The BLOG:

Early in Ray’s book, as he’s describing his early life and business experiences, one quickly realizes his path to the top was not a straight line. Quite the contrary. He hit rock bottom a few times too.

Ray suggests those experiences, when he nearly lost it all, were primarily the result of his insufficient understanding of history or historical context. After a painful loss, his research unearthed the fact that history had indeed repeated itself.

Consider this piece of history. In his book, Ray writes:

“Then, on Sunday, August 15, 1971, President Nixon went on television to announce that the U.S. would renege on its promise to allow dollars to be turned in for gold, which led the dollar to plummet. Since government officials had promised not to devalue the dollar, I listened with amazement as he spoke. Instead of addressing the fundamental problems behind the pressure on the dollar, he continued to blame speculators, crafting his words to make it sound like he was moving to support the dollar while his actions were doing just the opposite. “Floating it,” as Nixon was doing, and then letting it sink like a stone, looked a lot like a lie to me.”

Interestingly, while I lived thru this time, frankly I have no personal recollection of these events. Sure, I was young. Only about 14. Clearly, my desire to closely track current economic events had not yet matured. 🙂

Today it has so I decided to dig in deeper. What I found was a fascinating series of economic and political events, that began with the end of WW2 and ended in the early 1970s. During this period, America ascended to the peak of our financial power and generated about 1/2 of all global production; later, the US first began to consistently experience trade deficits; and, finally, in 1971, an event transpired which likely precipitated the beginning of the end of the United States as THE global financial powerhouse.

Let’s start at the end and work backward; here is what happened.

On the afternoon of Friday, August 13, 1971, Nixon and his cabinet made a few unprecedented decisions:

- They decided to “suspend” the convertibility of US dollar into gold. The “gold window” previously open to foreign governments holding US dollars was closed. Instantly and indefinitely.

- They enacted a 90-day freeze on wages and prices, an action intended to control inflation, the first time since WWII.

- They added an “import surcharge” of 10% to all goods and services being imported into the US — effectively a 10% tariff across the board.

Why did the US make these choices? And what were the long-term effects?

Let’s start with ‘why?’ Remember the US was deep into the Vietnam war during the 1960s. The financial cost of the war was staggeringly high. In order to pay for it, the FED increased US money supply. In fact, the FED increased money supply by over 50% in the 10 years preceding 1970. And this increase triggered a spurt in the inflation rate. By the mid-1960s, inflation had crept up into the 3s. And by 1970, inflation was flirting with 6%.

You may be thinking that an expanding money supply, as we’ve experienced in the past 10 years, does not, in itself, cause the inflation rate to spike. You would be right. But there was a unique difference between then and now.

Beginning at the end of WW2, the US dollar was convertible to gold at the “pegged” price of around $35 per oz. Even as more dollars were printed and circulated, the price of an oz of gold remained static. In 1960, one oz cost about $35. And here the price remained … until 1968 when an oz of gold jumped 22% to about $43. It remained in this range until Nixon’s announcement.

The second problem was more practical: Year after year, significantly more dollars began to circulate, both here and abroad. And as foreign nations increasingly swapped dollars for gold, the US was in a bit of a pickle. (Remember: As U.S. money supply increased, each dollar was worth less than it could buy in gold.) So countries around the world made the intelligent financial decision to swap bucks for gold. By 1971, the Nixon administration decided this was a serious problem. If this trend continued, the US would be out of gold and the US dollar would be completely debased.

I’m simplifying this a bit, as the 1960s were extremely turbulent from a monetary perspective. There was a new financial crisis just about every year — and gold seemed to be at the center of each crisis. (It’s worth noting that the U.S. owned about 65% of the world’s gold reserves a the end of WW2.)

Let’s get back to the Nixon speech. The following Monday, Nixon spoke to the nation. You can find both the YouTube video of the speech and the written content on the internet. Here are a few of Nixon’s comments to the American people:

- “We must protect the position of the American dollar as a pillar of monetary stability around the world.

- I have directed (Treasury) Secretary Connally to suspend temporarily the convertibility of the dollar into gold or other reserve assets, except in amounts and conditions determined to be in the interest of monetary stability and in the best interests of the United States.

- Now, what is this action — which is very technical — what does it mean for you? Let me lay to rest the bugaboo of what is called devaluation.

- If you want to buy a foreign car or take a trip abroad, market conditions may cause your dollar to buy slightly less. But if you are among the overwhelming majority of Americans who buy American-made products in America, your dollar will be worth just as much tomorrow as it is today. The effect of this action, in other words, will be to stabilize the dollar.”

I’ve highlighted a few terms above. First, notice the word temporary. No, the change was permanent.

Second, consider his comments about the devaluation of the US dollar when measured against foreign currencies. It was inevitable that the dollar would devalue…and his allusion to “take a trip abroad” was indicative of that fact. Vacations to Europe were going to cost a LOT more. The dollar may not have devalued within the United States, but, it took a huge hit when measured against currencies of other developed nations.

What I find fascinating is the comment that the “overwhelming majority of Americans … buy American made products.” Well, that’s changed, right? In order to “buy American” it has to be made in America. If we were at or near 50% in 1945, we’re probably closer to 15% today.

By 1973 the ‘European Economic Community,’ Japan, and the United States all agreed that their currencies would generally float without any tie to gold.

Recall that Japan was one of the strongest industrial engines at the time. Between 1945 and 1970, they rebuilt the country into a manufacturing powerhouse. One US dollar bought 15 yen when WW2 ended. By 1949, as their nation slowly recovered from the war and the yen devalued, 1 dollar bought 360 yen. Then, things changed. During the 1950s and 1960s, Japan hit their manufacturing stride. By 1971, the exchange rate was 1 dollar for 308 yen. And by the end of 1998, the US dollar now only bought 115 yen. That’s serious devaluation.

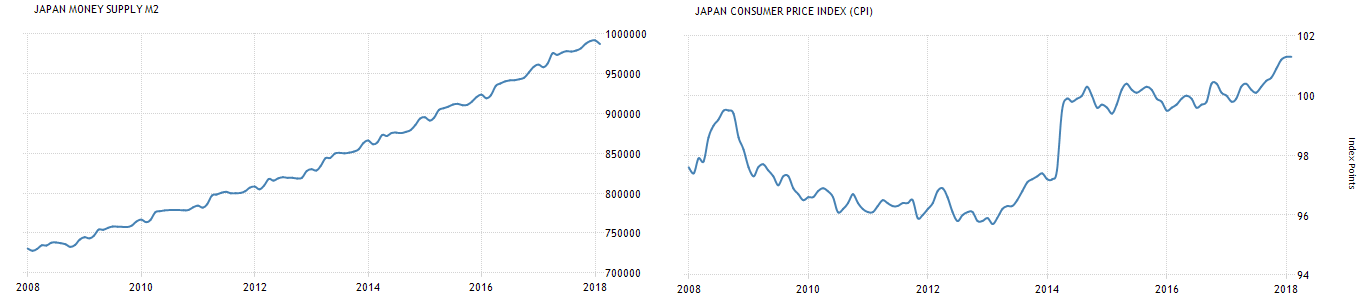

Unlike 50 years ago, when the USD had a $35 peg with gold, today money supply growth seems to be less correlated with inflation. Japan, in my opinion, proves this point.

Below are two 10-year graphs. The first shows Japan’s growth in money supply over the prior 10-years. Japan’s M2 began 2008 at 740,000 billion yen. It began 2018 at close to 990,000 billion — an increase of 33.7%. Yet, over the same period, the Japanese CPI increased by maybe 3%.

Make no mistake: Money supply growth does matter. Consider Venezuela and Zimbabwe. Apparently there is some tipping point after which inflation begins. Japan simply hasn’t found it yet. And clearly there is a tipping point after which hyperinflation is triggered.

It’s interesting to note our success in WW2 lifted the US to our financial pinnacle. The cost of our error in Vietnam was the beginning of the end of our hegemony.

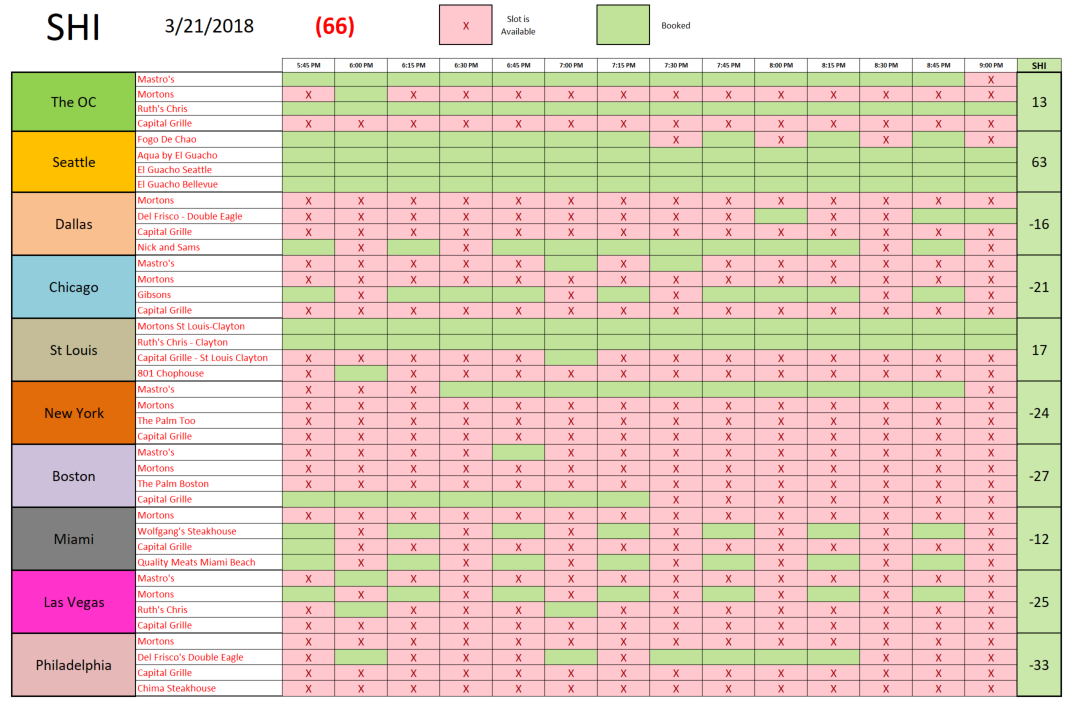

OK…I’ll get back to my final points below, but first, let’s take a trip to the steakhouses. One thing is obvious from the grid below: Man, do they LOVE expensive steaks in Seattle!

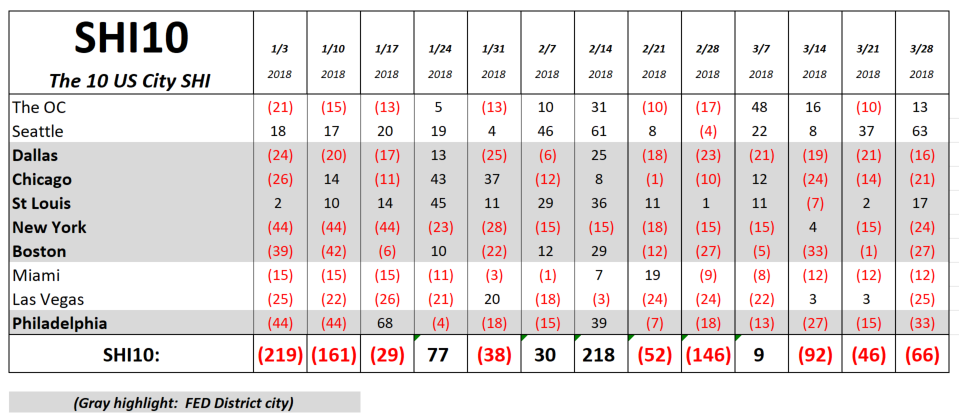

Look at that Seattle SHI reading: A 63! I don’t think we’ve ever seen a number that high before. Even the OC had a good week. But once again our pricey eateries in the east had a tough week. We’ll have to see how spring affects east coast consumer demand as the weather improves. Here is our longer term trend grid:

It’s easy to see consumer demand and spending has been relatively consistent over the past few weeks. Not great … but not poor either. Fairly “steady as she goes” so to speak.

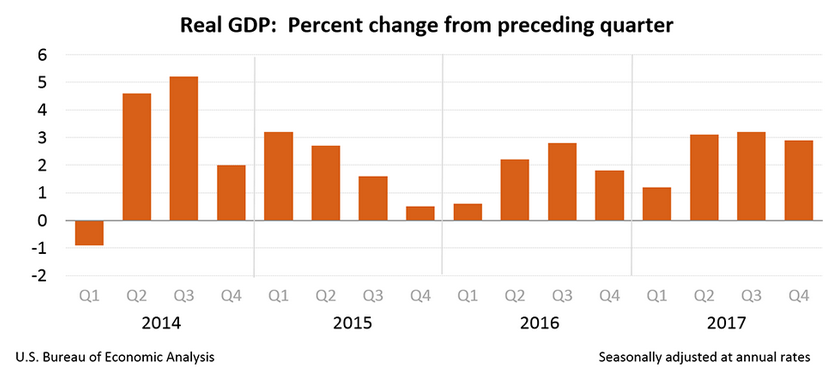

Consistent, too, with this morning’s “final” Q4 GDP reading posted by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). In Q4, our GDP grew by 2.9%, a bit higher than the previously reported 2.7%. Here’s the chart:

And our nominal GDP grew to $19.754 trillion by the end of 2017. Interestingly, nominal GDP grew by about $250 billion in both Q3 and Q4. Annualized, this is a run rate of a $1 trillion GDP increase.

For now, I have strong confidence this will continue. Both the SHI10 and other general economic indicators suggest this outcome. But Ray Dalio would ask if there are storm clouds forming on the fringe of the horizon….

Here is my concern: From a financial perspective, we have repeated the “Vietnam mistake” in the middle east. This has proven to be a long and expensive war, and once again we have racked up a huge bill. I’m not debating the post-9/11 decision to engage terrorism at its source. I’ll leave that to you. I’m simply saying we may find the long-term cost of this choice may exceed our ability to pay.

And how will this “inability to pay” issue manifest itself?

First, let me be clear, I don’t believe this problem will manifest any time soon.

Many conditions are different today than in 1970. Currencies float and find their own “value” level. Sort of. (This, again, is another long discussion.) And, of course, the value of gold floats, too.

This is different too: The US Treasury is issuing record-setting quantities debt securities to cover our annual deficit. This week the Treasury will sell $294 billion of ‘notes’ and ‘bills’ — shorter term securities. And this is happening simultaneously with the FED shrinking it’s balance sheet, reducing its holdings by about $20 billion each month. Both actions reduce money supply. Remember, Japan’s central bank is buying almost all of the issued debt. Japan is increasing their money supply hoping to trigger inflation. After years of easing, we’re now doing the opposite. We are now shrinking US money supply.

Thus, we probably don’t have much concern about money supply triggering an inflationary spiral. For now. But what other problems might a $1 trillion 2018 deficit cause? And what if this is the first year of many similar annual deficits? What might be the outcome and result?

Could we be witnessing history repeating itself?

I’m sure these are questions Ray would suggest we ponder today. In his book, Ray opined, “You better make sense of what happened to other people in other times and other places because if you don’t you won’t know if these things can happen to you and, if they do, you won’t know how to deal with them.”

Our politicians seem less concerned about the tipping point than I am. Maybe I’m just a worrier. A party pooper. But I suspect Ray might agree with me.

– Terry Liebman